Introduction

Recent advances in Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) have opened up powerful new ways to access cultural heritage material. HTR models can now achieve high levels of accuracy in transcribing handwritten texts, making once difficult-to-decipher historical archives searchable in ways that resemble the granular digital search we take for granted online (Nockels, Gooding, and Terras 2024). At the Swedish National Archives’ AI lab, our colleagues have spent the past few years significantly improving HTR models for modern and early modern Swedish. The technology is now being applied at scale, with over a million documents set to be transcribed and made digitally searchable.

But what about older handwritten archival holdings? The National Library of Sweden (KB) has over 300 medieval manuscripts, many of which remain challenging to search, analyze or even read due to the complexity and variability of the writing style. At KBLab we have begun exploring the possibilities of HTR to enhance the searchability of this material. In particular, we have been testing and comparing existing HTR models for Latin texts to establish the state of the art among openly available tools. This forms part of our broader mission to improve access to the library’s digital collections by harnessing the capacities of AI (Börjeson et al. 2024).

In this post, we present some initial results from our experiments, highlight key challenges and share insights into the potential and limitations of HTR for Latin manuscripts. Before assessing these models, we begin with a brief overview of the library’s Latin manuscript holdings and an introduction to how HTR techniques work.

KB’s Latin manuscripts

Around 60% of KB’s medieval manuscripts are written in Latin. These span from the early eighth century to the late sixteenth century and include texts on theology, law, grammar, philosophy, medicine, astronomy and rhetoric (Böckerman 2025). The largest subgroup consists of theological manuscripts - about 200 in total. As part of an ongoing effort to improve access to these materials, a project is currently underway to provide detailed catalog descriptions and full digitization of all theological Latin manuscripts in the collection. Once digitized, the materials are made available through the library’s digital research infrastructure: manuscripta.se. The project, funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, involves a team of Latin specialists at KB and is scheduled for completion in 2026.

From the 8th to the 15th century, Latin manuscripts were written in a variety of scripts that reflect shifts in writing styles. Between 700 and 1000, the dominant script was Carolingian minuscule - a relatively clear and legible hand. Yet KB holds only a few manuscripts from this early period. In the following centuries (1000–1200), the so-called protogothic script emerged. This transitional style is important but still relatively understudied, and the library’s manuscripts from this period are also limited. The majority of Latin manuscripts at KB -roughly 90 - date from 1200 to 1500 and are written in various Gothic scripts. These include the highly formal textualis (often used for liturgical purposes) and the more practical, everyday cursiva. In the 15th century, the humanist minuscule - developed in Italy as a deliberate return to earlier Carolingian and protogothic forms - appears as well. This style is notably more legible, and the library holds a few examples written in this hand.

Saint Birgitta - or Bridget of Sweden, as she is often referred to in international contexts - lived in 14th-century Sweden and, beginning in the 1340s, is said to have received a series of divine visions. She initially recorded these revelations in Swedish, which were later translated into Latin. The Latin version became the standard text and circulated widely across Europe, contributing to Birgitta’s growing international influence.

We selected a few pages from five Latin manuscripts (A 32, A 66, A 68, A 69, A 70) containing The Revelations by St. Birgitta of Sweden to explore how well automatic text recognition can be applied to Latin manuscripts in the library’s collections. The aim was to assess whether existing HTR models could handle the complexity and variation typical of medieval Latin texts, and to identify which models might serve as suitable starting points for future fine-tuning.

HTR architecture

HTR is a form of optical character recognition (OCR) designed to convert handwritten text into machine-readable formats. In recent years, HTR has seen significant advancements - evolving from early rule-based and statistical approaches to deep learning and transformer-based architectures.

Early HTR systems relied heavily on handcrafted features, lexicons, and probabilistic models such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), often combined with n-gram language models. The advent of deep learning marked a major turning point. In particular, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) - especially Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks - enabled models to extract features directly from raw image inputs and to capture the sequential nature of handwritten text lines. This architecture significantly improved recognition accuracy, especially for more challenging handwritten scripts and historical manuscripts.

More recently, transformer-based models - such as TrOCR - have pushed the boundaries of what HTR systems can achieve. Unlike traditional RNNs, transformer models rely on self-attention mechanisms that capture long-range dependencies in sequences more effectively (Vaswani et al. 2017).

These technical advances have been supported by the increasing availability of annotated training datasets, the synthetic generation of handwritten texts, and platforms such as eScriptorium, Transkribus, and the Hugging Face Model Hub, which enable the training, fine-tuning and deployment of HTR models.

HTR process

HTR models can operate at different levels - character, word, line or page. The models we tested are mostly line-level, so we’ll focus on how that process works.

To recognize text from a manuscript page using a line-level model, the first key step is segmentation. This means breaking the page down into parts the model can actually read - starting with identifying where the text is and then splitting it into individual lines. Segmentation has two main components:

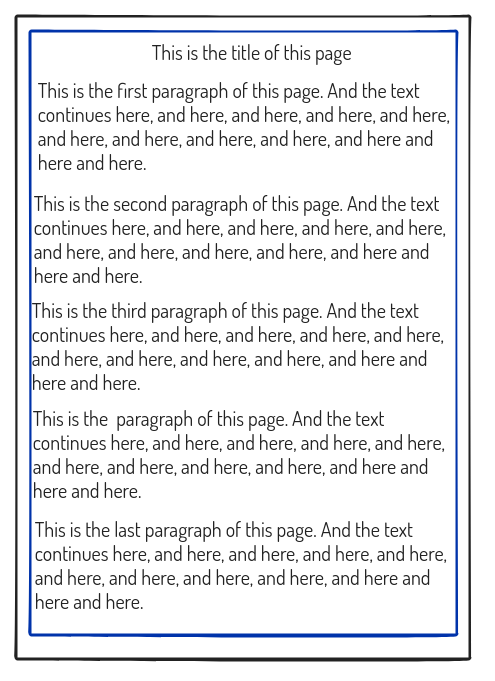

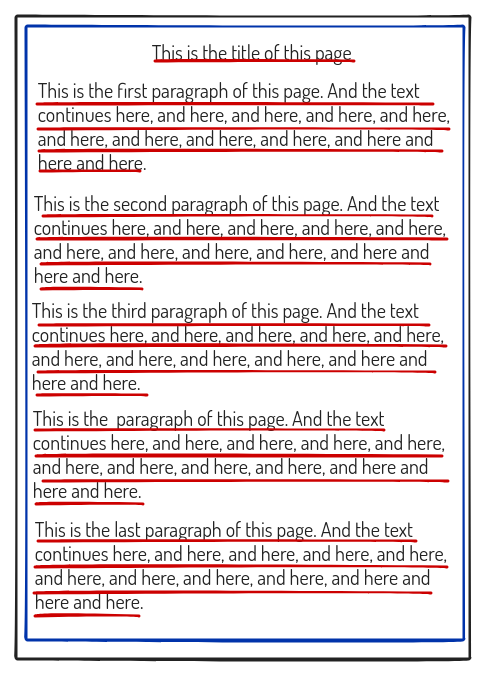

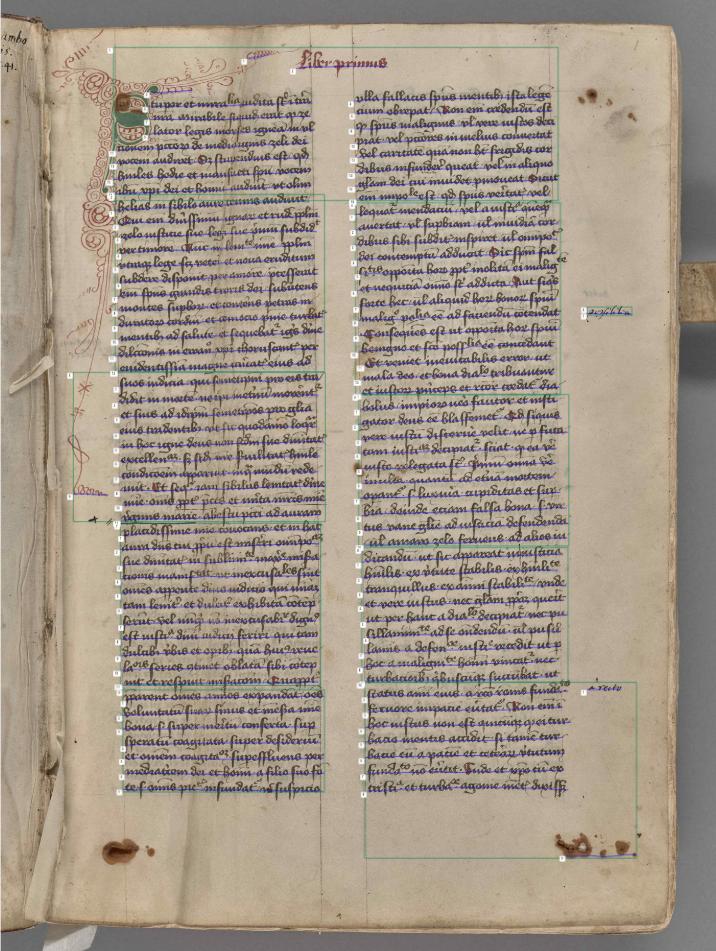

Region detection: Identifying blocks of text on the page and separating them from non-textual elements such as images, margins and decorations etc (see Figure 1 (a)).

Line extraction: Finding each individual line of text within those regions and cropping them out as individual images (see Figure 1 (b)).

Segmentation is crucial because it also determines the reading order. Line-level HTR models process one line at a time and have no built-in understanding of sequence. So if the segmentation process gets the reading order wrong, the final output will not make sense.

Tools like eScriptorium or custom setups using object detection models like YOLO - You Only Look Once (Redmon et al. 2015) - can handle the segmentation process. These tools often allow manual adjustments, which is especially useful for complex layouts in historical documents.

Once the lines are segmented, they are passed to the HTR model, which reads each line image and outputs the recognized text. Some platforms also use language models to refine grammar, predict words or assign confidence scores that flag uncertain results for human review.

Finally, the transcribed lines are reassembled to reconstruct the full page of handwriting as digital text. As suggested, this final output relies heavily on accurate segmentation from the start. Without the correct reading order, we cannot expect a legible text at the end of the process.

Challenges with HTR and Latin manuscripts

One of the main challenges in applying HTR to Latin manuscripts is the sheer diversity of handwriting styles, typescripts and scribal conventions, which can vary significantly even within a single document or collection. This variability makes generalization difficult - models trained on one set of manuscripts often struggle to adapt to others without retraining or fine-tuning.

For instance, a model trained on Carolingian minuscule - a relatively open and legible script used between the 9th and 12th centuries - may perform poorly when applied to Gothic textualis, a denser script that emerged later and features tightly packed letters, numerous ligatures and frequent abbreviations. Even within the Gothic tradition, different writing styles such as the more formal textualis and the faster, less consistent cursiva present distinct challenges. Early modern humanist scripts, which deliberately revived classical letterforms and often resemble modern fonts, might seem easier to read at first glance. Yet even these show variation in letter shapes - such as long s versus short s or u versus v - and are often accompanied by marginal notes in entirely different hands.

Another complicating factor is the way manuscripts are transcribed. Transcriptions can vary significantly in their level of editorial intervention, which in turn influences how models are trained and evaluated. A diplomatic transcription preserves original spellings, abbreviations and letterforms, aiming to capture the text as it appears in the manuscript. A semi-diplomatic transcription may expand some abbreviations or regularise spelling for readability, whereas a normalised transcription modernises the text to align with contemporary orthographic standards. Abbreviations are expanded, non-standard characters are replaced with modern equivalents, and spacing, punctuation and capitalisation may be adjusted. While this makes the material more accessible for modern readers and analysis, it may strip away useful palaeographic information.

Abbreviations themselves pose a specific challenge. Latin scribes used a wide array of abbreviation marks to save time and space, and these are not always easy for an HTR model to detect or interpret. Whether a model expands or retains them often depends on the transcription style it was trained on.

Taken together, the variability in scripts, transcription practices and scribal habits means that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to HTR rarely works for Latin manuscripts. Instead, models need to be adapted to the specific characteristics of the material - for particular writing styles, time periods or even individual scribes. Though such fine-tuning of models is a time-consuming process, it is necessary to produce meaningful and accurate automatic transcriptions. Tools and platforms like eScriptorium, Transkribus, and Hugging Face now offer increasingly accessible ways to train and customize HTR models to meet these challenges.

Different HTR frameworks

Transkribus

Transkribus is a platform maintained by READ-COOP SCE (Recognition and Enrichment of Archival Documents – Cooperative Society), a European cooperative focused on advancing research and innovation in the digital humanities. The cooperative brings together a broad community of academic institutions, cultural heritage organisations, archives and individual researchers, with the goal of making historical documents more accessible and understandable through digital tools.

The platform offers tools for transcription, annotation and analysis of historical documents. One of its core features is support for HTR, enabling users to train and apply models tailored to specific handwriting styles in order to automate transcription.

Transkribus operates on a credit-based system: users receive a number of free credits, and larger or more complex projects can be supported through a range of paid plans.

The platform relies on PyLaia, a recognition engine developed by the Universitat Politècnica de València. Currently, Transkribus hosts more than 200 publicly available models, which can be used directly or fine-tuned to new handwriting styles or collections. However, it’s also worth noting that models trained within Transkribus are designed to work exclusively within the platform.

eScriptorium and Kraken

Like Transkribus, eScriptorium is a platform designed to manage transcription workflows. It supports both manual and automated processes for annotation, segmentation and model training. The software was developed as part of the Scripta project at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres (EPHE–PSL).

eScriptorium is open source and can be installed locally. For light tasks such as annotation, segmentation or transcription, no specialised hardware is needed - standard consumer-grade computers are sufficient. Model training can also be done on CPUs, though the process is significantly faster when using GPUs, especially for large datasets or multi-user environments.

The underlying recognition engine in eScriptorium is the OCR software Kraken. Kraken uses deep learning, specifically recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with connectionist temporal classification (CTC), to recognise text in images. It offers flexible layout analysis and supports training on custom datasets, making it well suited for historical documents and complex scripts.

Pretrained models compatible with eScriptorium are often shared through repositories like Zenodo, typically alongside the training data used to create them. These resources - produced by researchers and institutions as part of larger transcription projects - can serve as helpful starting points for similar materials. Using such models can significantly reduce the time and effort required for training, particularly when working with rare or difficult scripts.

Once uploaded to eScriptorium, models can be used directly for transcription or fine-tuned on new data.

Advanced HTR training options

Platforms such as Transkribus and eScriptorium provide graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that lower the technical barrier, allowing users to train Kraken or PyLaia models without writing code. But for those who need greater control over the training process - hyperparameters, preprocessing pipelines or custom architectures - both Kraken and PyLaia can be run independently of these platforms. However, PyLaia models trained within Transkribus cannot currently be exported, so external training requires either building your own model from scratch or fine-tuning one from outside that ecosystem.

For an approach that works directly with Python packages, you can also leverage Microsoft’s transformer-based TrOCR models via the Hugging Face Transformers library. These models come pre-trained on a mix of printed and handwritten datasets and can be fine-tuned on your own Latin manuscript images to boost performance on complex, historical scripts. TrOCR’s transformer-based architecture allows them to handle complex input more robustly than some more traditional OCR approaches (Li et al. 2021).

Because most line-level HTR models assume correctly segmented inputs, they need to be paired with a region-detection step. Object-detection models like YOLO can locate and crop text regions or individual lines in a page image. Once each line has been detected and isolated, any of the above HTR models - whether trained via a GUI platform or directly in Python - can be applied to produce the transcription.

Testing eScriptorium

Having provided an overview of available HTR tools, we now turn to how these models perform in practice when applied to KB’s Latin manuscripts. In the remainder of this post, we discuss our experiences using eScriptorium, Transkribus and TrOCR’s models for automatic transcription.

Segmentation

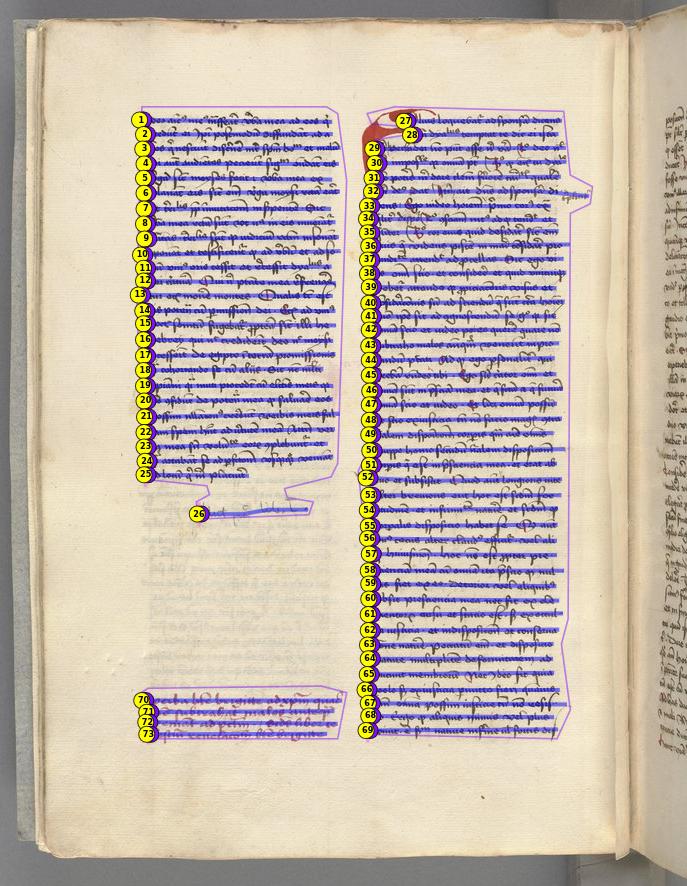

Before comparing the models themselves, let’s first examine the segmentation process. For our experiments, we used Kraken’s default segmentation model, available on Zenodo. This model predicts a single region class and is designed to work well on most non-fragmentary handwritten and machine-printed documents with moderate layout complexity. (It can also serve as a good starting point for fine-tuning when necessary.)

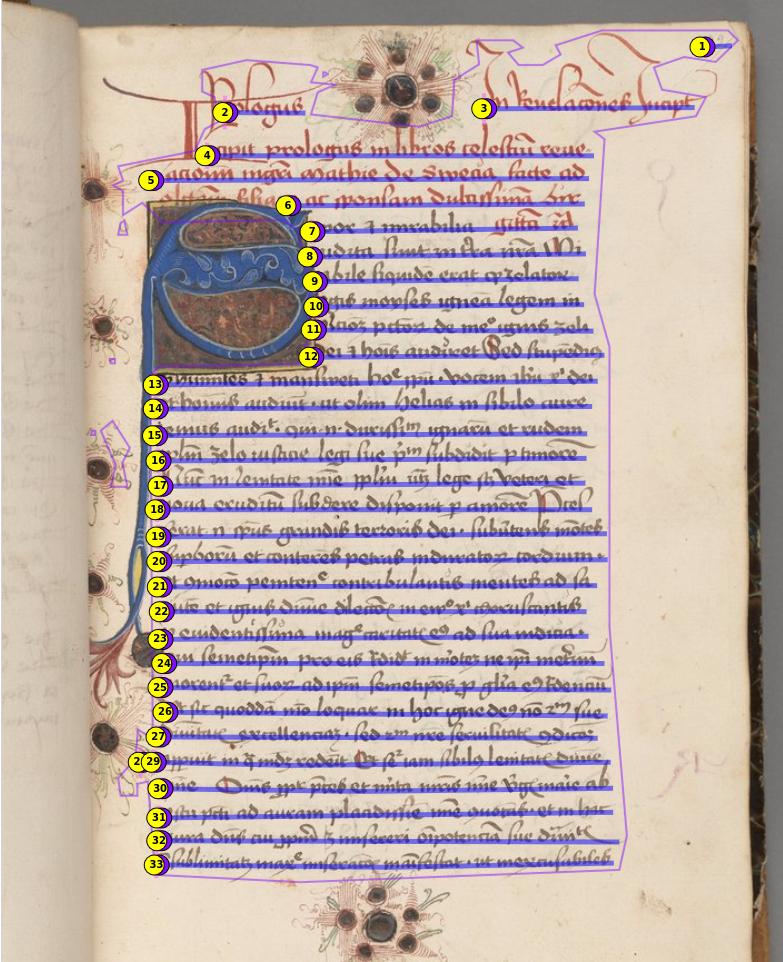

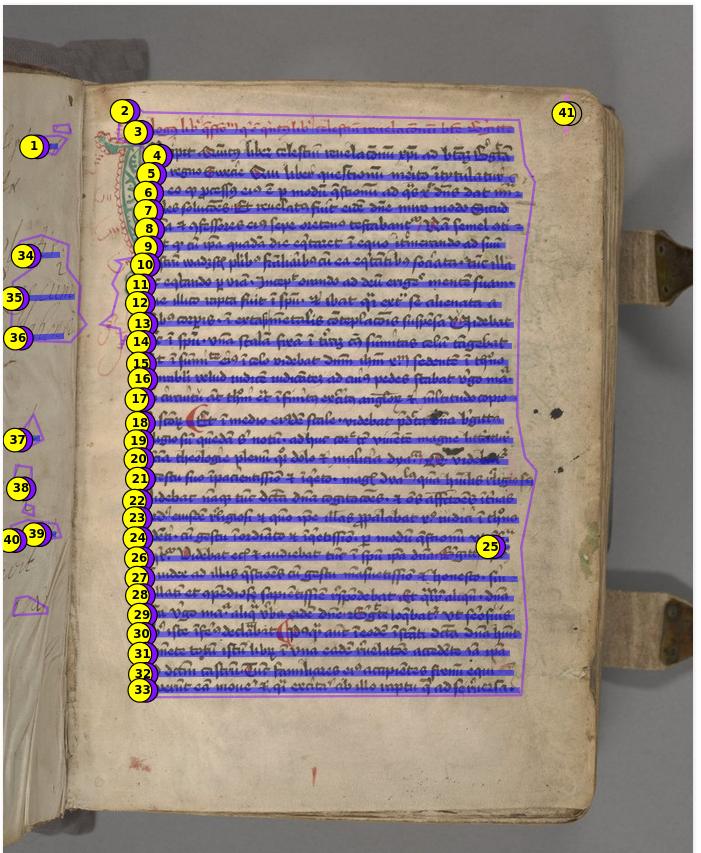

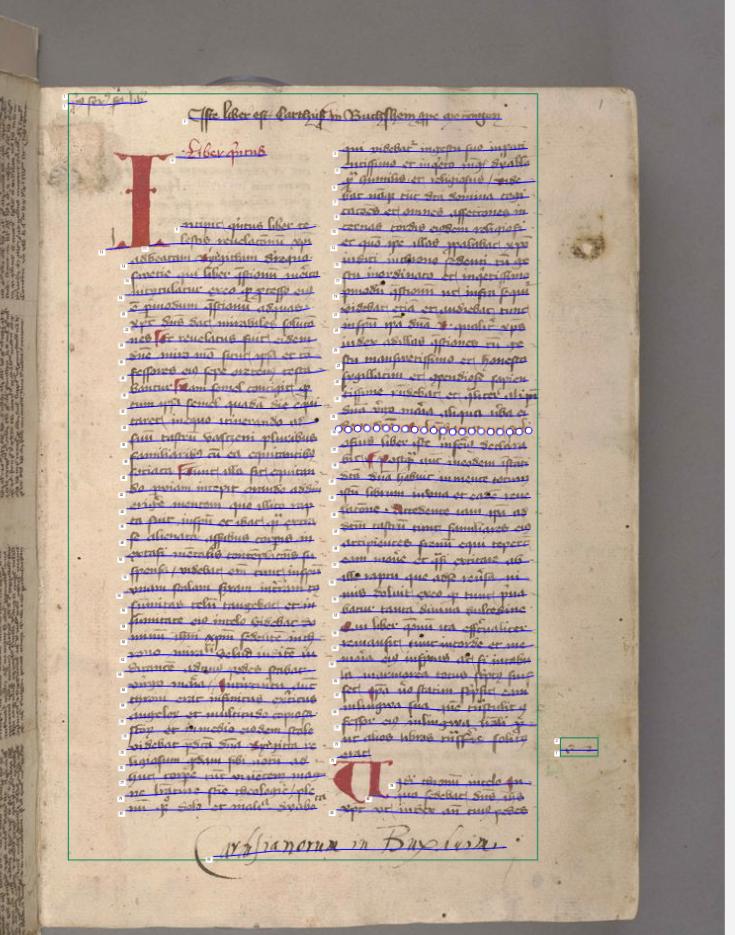

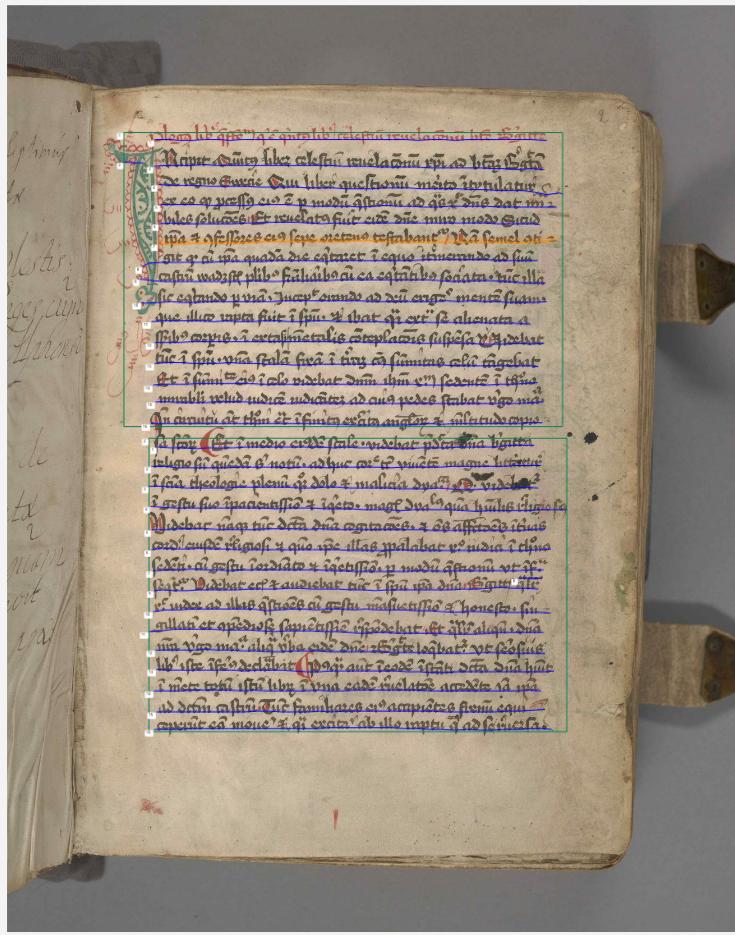

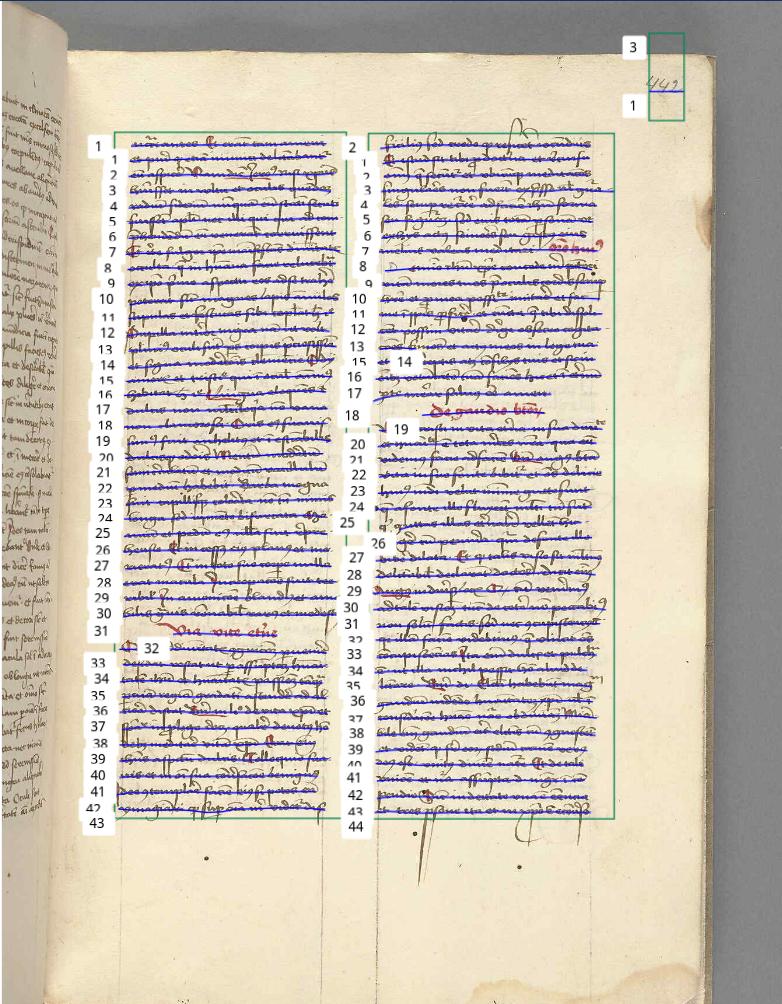

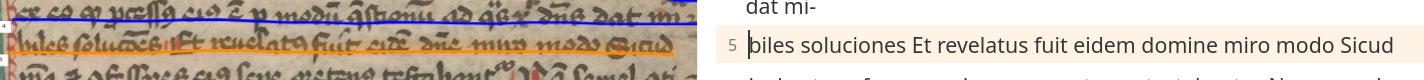

We applied the model to two single-column pages and three double-column pages. The images below show how the segmentation output highlights detected regions (in violet) and text lines (in blue). The yellow circles indicate the proposed reading order, which determines the sequence in which the transcribed lines will be arranged.

Single-column manuscript pages

On the single-column pages, the segmentation model performed reasonably well. Almost all lines of text were correctly enclosed within a single region, with no major omissions (see Figure 2 (a) and Figure 2 (b)). This suggests good generalisation for straightforward layouts. In one case, however, the model mistakenly recognized regions on the previous page, which will later affect the reading order.

Reading order and line association

An important feature of Kraken’s layout analysis is the way it organizes regions and lines. While reading order typically proceeds from top to bottom, indentations or more complex layouts - such as double columns - can lead to unexpected results. A line can either be associated with a region or classified as an orphan. Regions themselves can contain multiple lines, a single line, or none at all. When lines are associated with a region, their reading order is calculated within that region, not across the entire page.

This makes segmentation a critical first step for producing a coherent transcription. If regions are too broad or incorrectly identified, the resulting reading order will become confused.

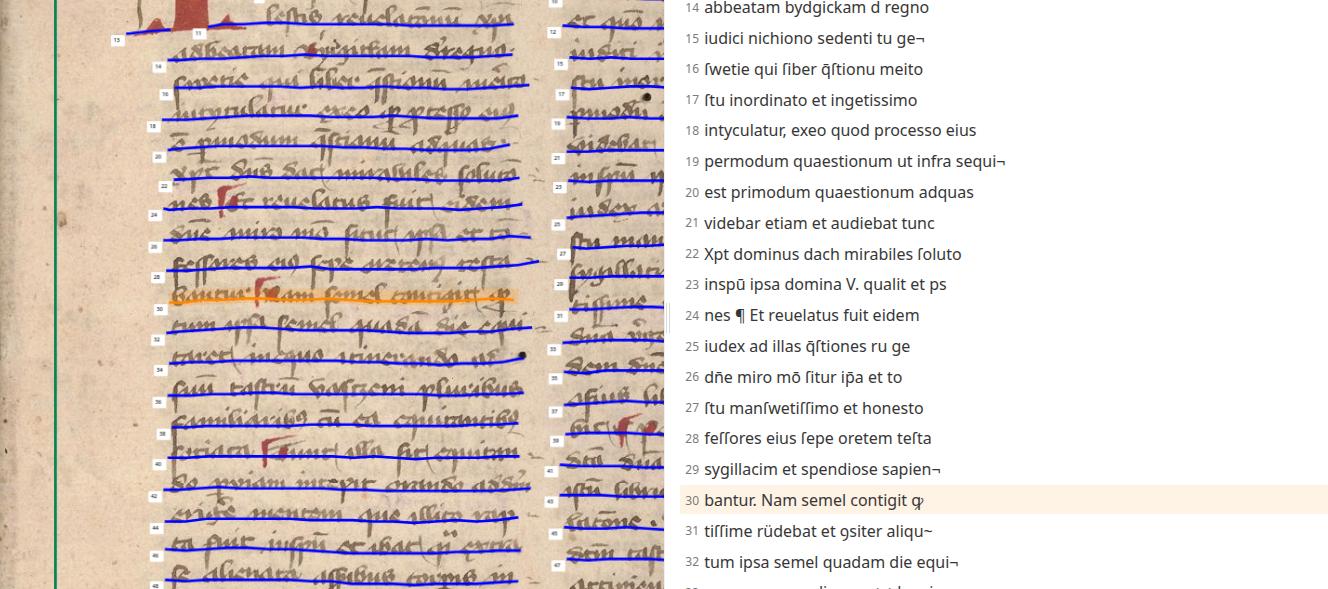

Double-column layouts illustrate this well. In Figure 3 (a), the model correctly identifies three distinct regions, assigning them a logical reading order. But in Figure 3 (b), the model encloses the entire page in a single region, ignoring the column structure. As a result, the lines are read left to right across the page, rather than top to bottom within each column - producing a disordered output.

In addition to problems with reading order, some lines are not properly segmented: a few are merged across both columns, while others are omitted altogether. These examples highlight the limitations of the default segmentation model when applied to complex or irregular layouts, and suggest that fine-tuning may be necessary for improved performance.

Transcription

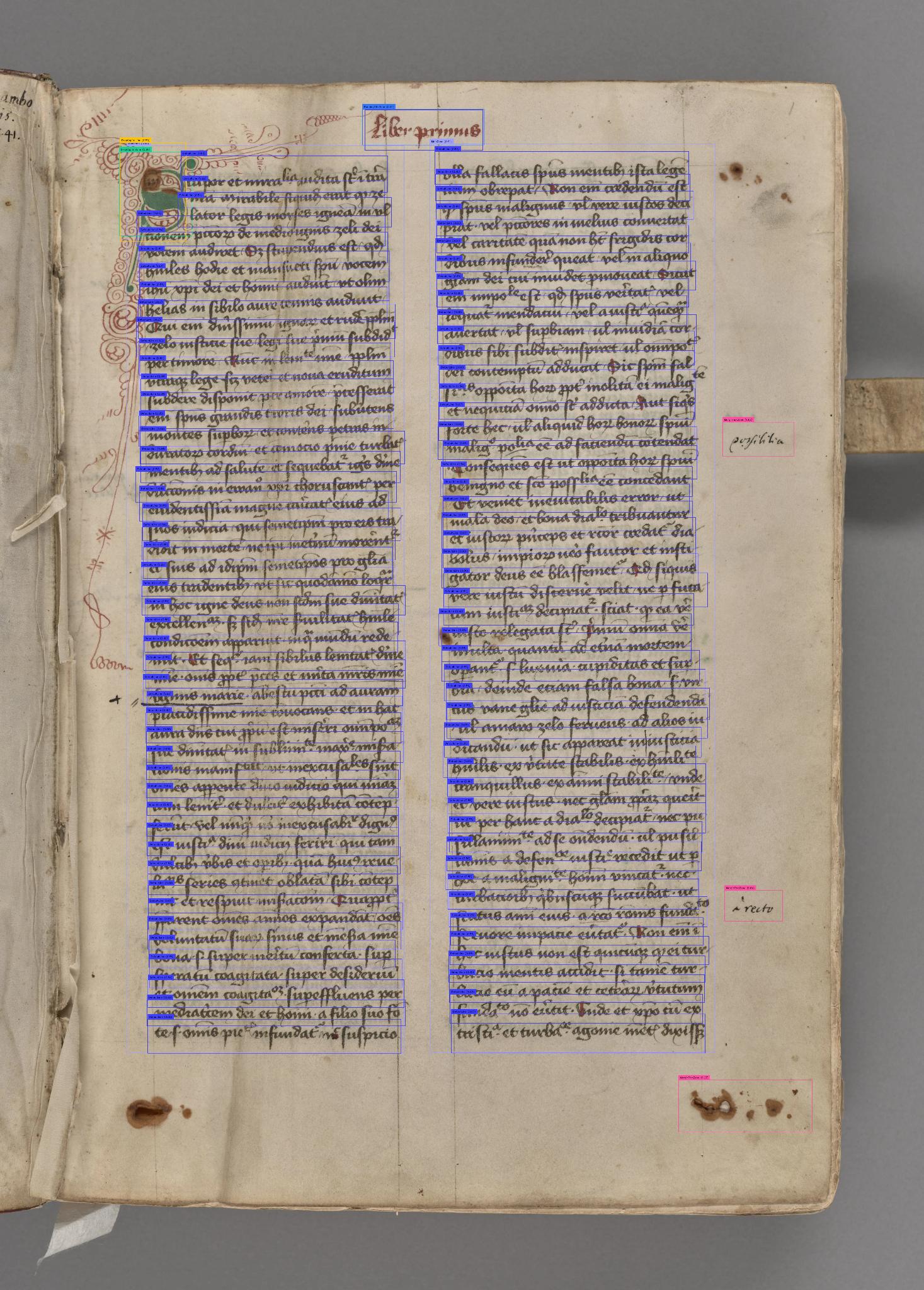

Once segmentation is complete, we can proceed with transcribing the documents. We tested several models available on Zenodo, each trained on different Latin manuscript datasets. The two best-performing models were TRIDIS and CATMuS, which also exemplify two different approaches to transcription and annotation.

TRIDIS (Tria Digita Scribunt) is a multilingual HTR model trained on semi-diplomatic transcriptions from medieval and early modern documentary manuscripts. This means it retains much of the original spelling and character forms, while also expanding some common abbreviations and smoothing out inconsistencies to improve readability and support downstream analysis. TRIDIS is especially suited to legal, administrative and memorial documents from the 13th to 16th centuries, but it has also been shown to perform well on other genres, including literary texts, cartularies and scholarly treatises.

In contrast, CATMuS Medieval (Consistent Approach to Transcribing ManuScript) takes a stricter approach. It is trained on graphematic transcriptions that reproduce each character exactly as it appears in the manuscript - without expanding abbreviations - and represent diacritics, superscripts and ligatures separately using NFD Unicode normalization. CATMuS supports multiple languages, including Latin, Old and Middle French, Spanish and Italian, and reflects a consistent transcription standard developed across several collaborative projects, such as CREMMA, HTRomance and GalliCorpora.

One thing both models have in common is the scale and breadth of their training data. Compared to the other models we tested, TRIDIS and CATMuS were trained on significantly larger datasets: around 560,000 lines of Latin text for TRIDIS and 160,000 for CATMuS. By contrast, a third model we tested was trained on approximately 46,000 lines, of which fewer than 10,000 were in Latin. As expected, its performance was noticeably weaker. This highlights the importance of dataset size in enabling better HTR performance.

Results of HTR with Kraken Models in eScriptorium

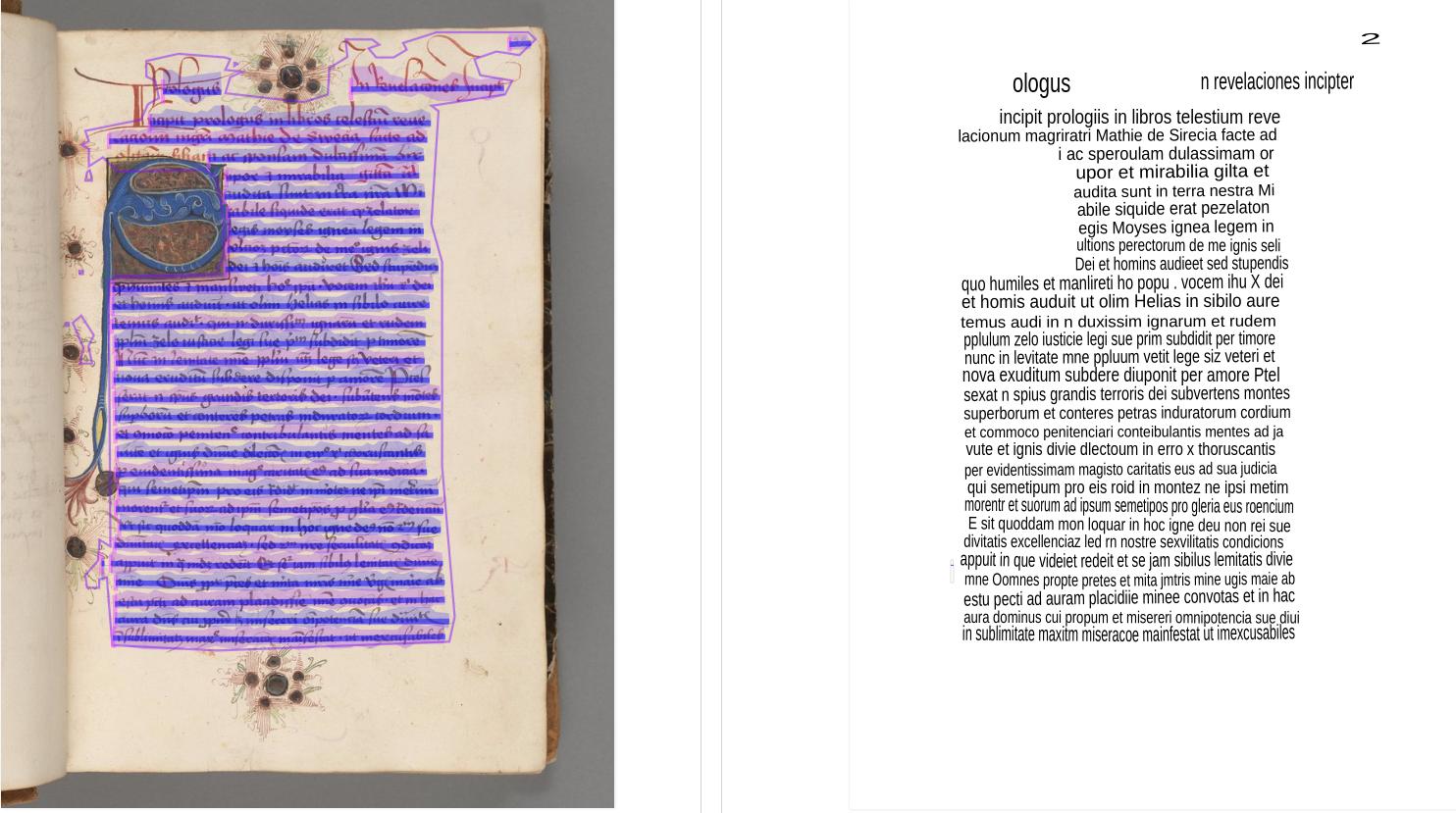

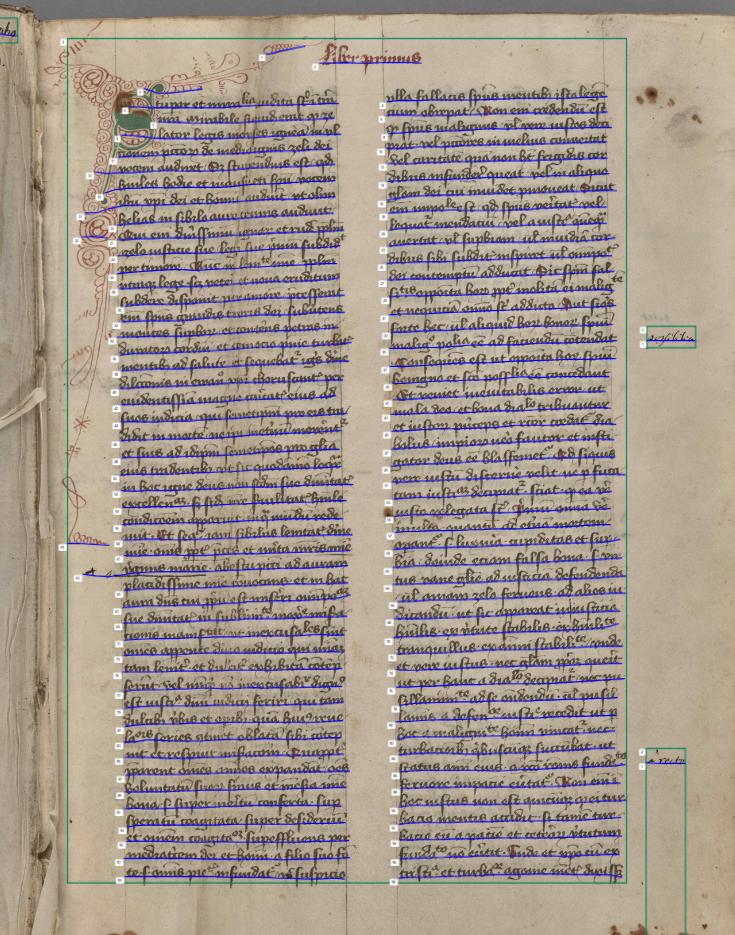

As noted above, off-the-shelf HTR models tend to perform best on material similar to their training data. Since we have not yet fine-tuned any models on KB’s manuscripts, perfect results are not to be expected at this stage. Instead, our aim is to survey the current capabilities of available Latin HTR models and determine which might be best suited for fine-tuning to better match the characteristics of KB’s collections.

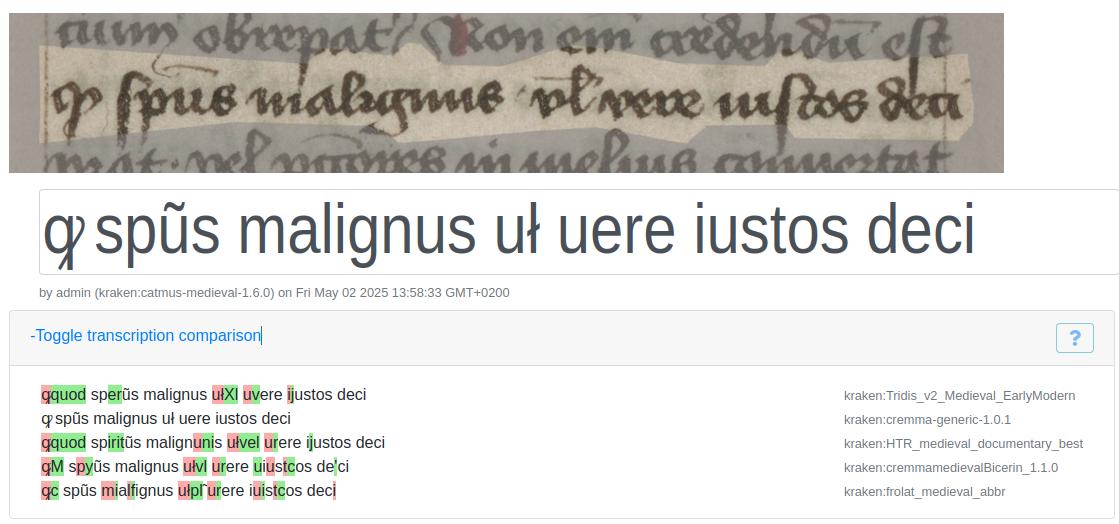

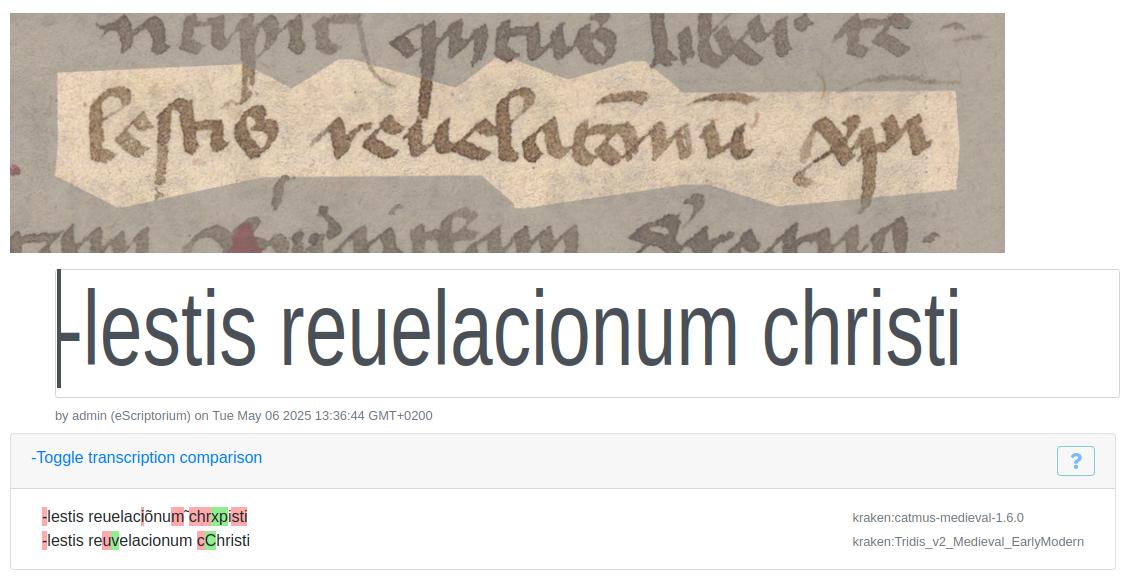

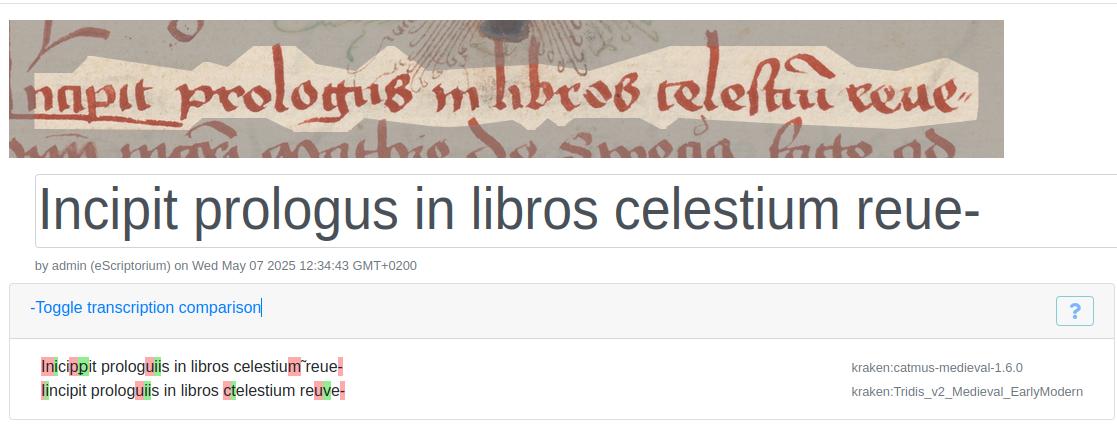

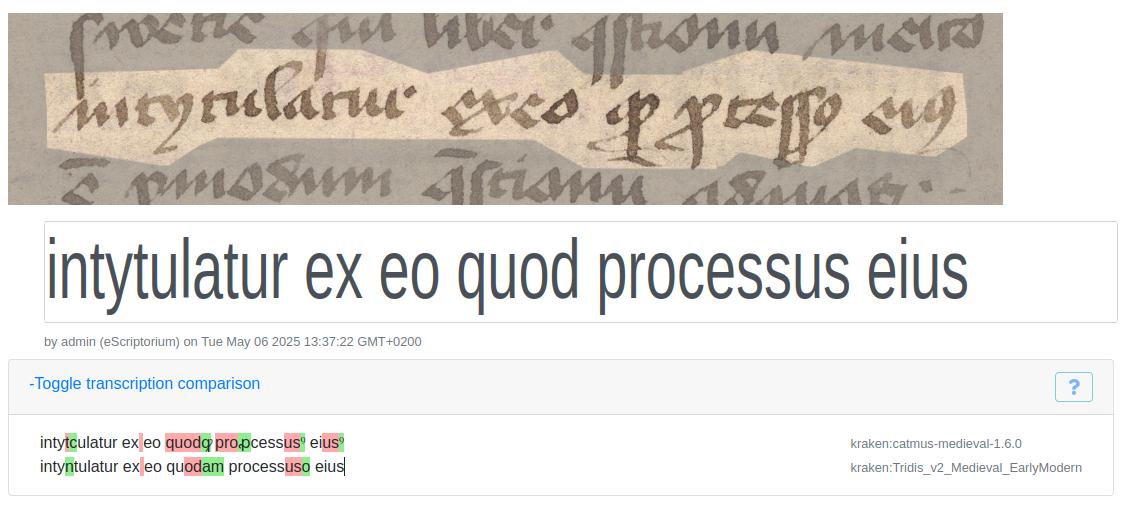

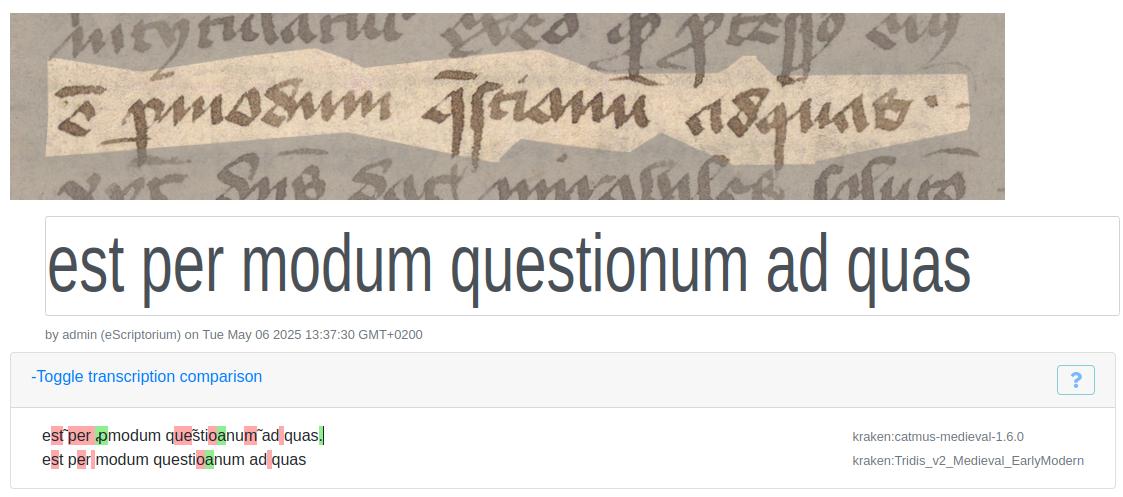

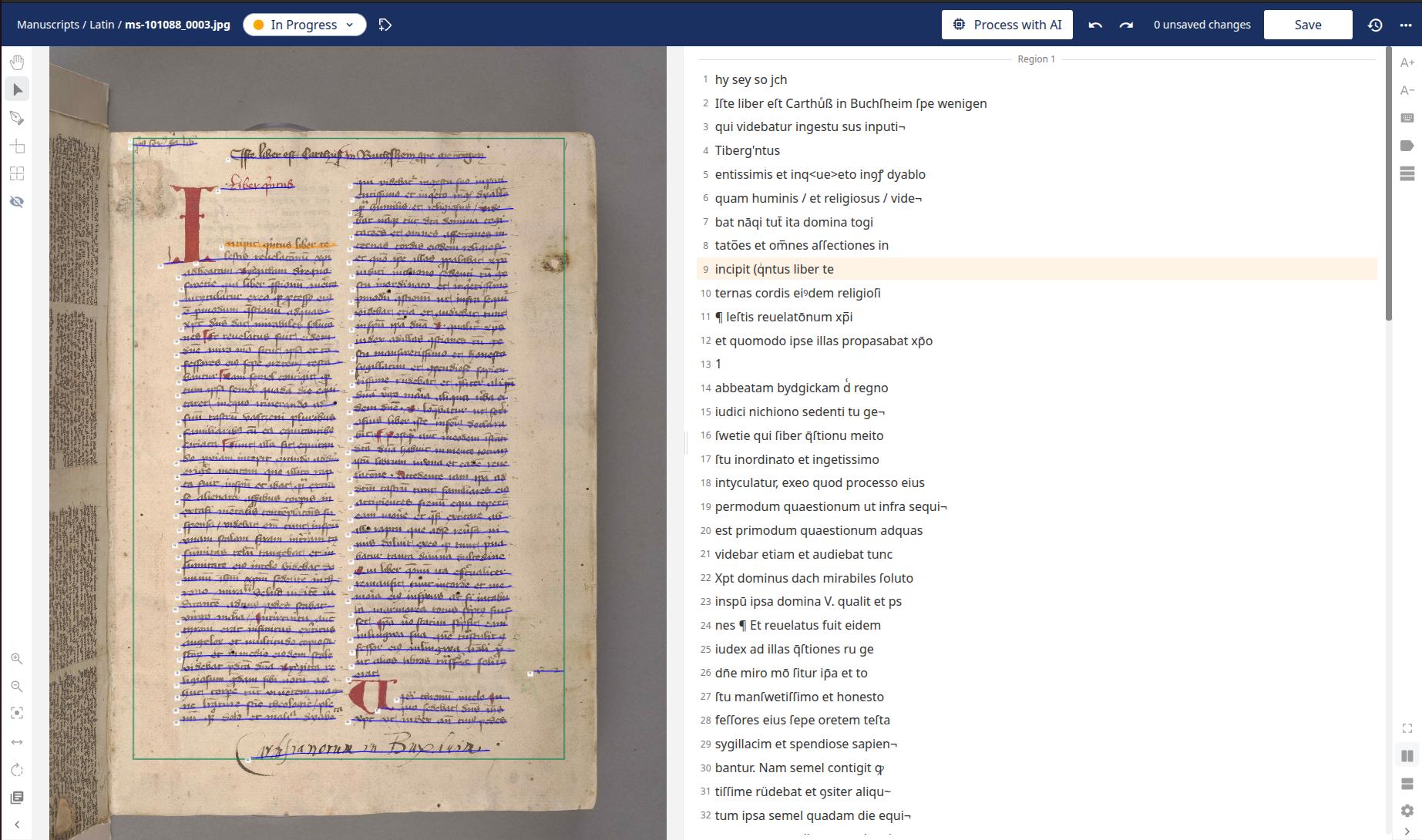

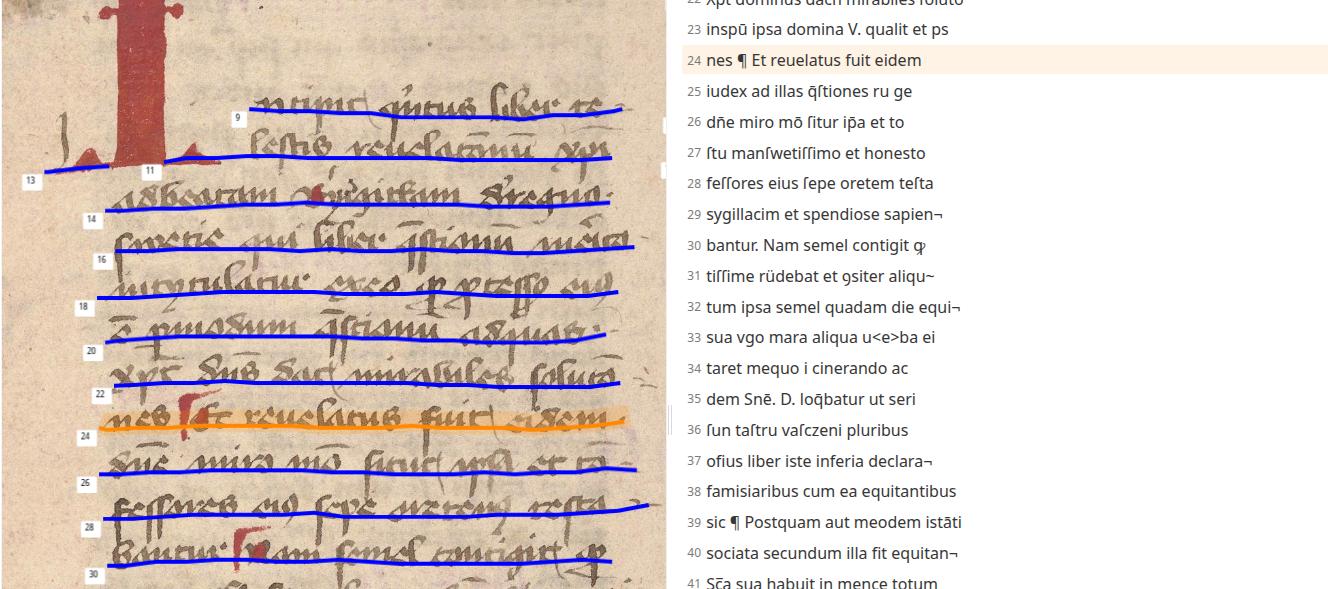

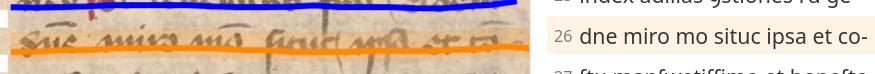

The user interface of eScriptorium makes it simple to compare the outputs of different HTR models. As Figure 5 shows, the GUI displays a manuscript excerpt alongside a manual line-by-line transcription and the results from various models (e.g., catmus_1.6.0 and tridis_v2). Insertions are highlighted in green, deletions in red. In our experiments, all manual transcriptions were done line by line, with hyphens marking words split across lines. Abbreviations were expanded - though without special notation - and the original orthography was preserved throughout.

We used this interface to compare transcriptions produced by CATMuS and TRIDIS, and we present a series of examples from that comparison below.

Various factors need to be considered when assessing these outputs. Because each model follows its own transcription conventions, red and green highlights don’t always signal true errors. CATMuS, for instance, emits graphematic output as opposed to expanding abbreviations - so in the example above “xpi” remains unchanged rather than expanded to “christi” (see Figure 6), and diacritic-driven omissions (e.g. ◌̃ for an omitted “m”) are left in their original form. Likewise, differences in capitalization or in rendering “i” as “j” and “u” as “v” reflect annotation choices rather than model failure.

Segmentation errors can further complicate evaluation. In Figure 7 and Figure 8 above, the words “Prologus” and “Incipit” lie partially outside the detected text region. Because the model never “sees” the full word image, it predictably fails to transcribe it correctly - underscoring how even the best HTR engine depends on accurate region detection.

Let’s consider a few more examples. Across several excerpts, we observed various model-specific quirks:

- The LATIN word “quod” (‘that’) was transcribed by CATMuS as the abbreviation “ꝙ,” while TRIDIS misread the same sign as “ꝗ” and expanded it to “quam” (‘how’) (see Figure 9).

- The symbol “ꝰ” intended as “us” was rendered simply as “o” in TRIDIS’ expanded transcription, whereas CATMuS correctly preserved the meaning of both “processus” and “eius”.

- In Figure 10 below, the scribal abbreviation for “est” (‘is’), ẽ, was correctly recognized by CATMuS but not TRIDIS. However, neither model detected the “per” abbreviation, p̱, leading to mistaken readings of “ꝓ” or plain “p.”

Other errors - such as concatenated words or confusion between similar strings like “quam” vs. “quod” - further illustrate the gap between generic models and our specific manuscripts. Yet these results also point to a clear path forward: fine-tuning on annotated data from the same scribal hands should markedly improve accuracy. In sum, while base Kraken models offer a useful preview of HTR performance on KB’s Latin holdings, sustained fine-tuning is likely essential for reliable, high-quality transcriptions.

Testing Transkribus

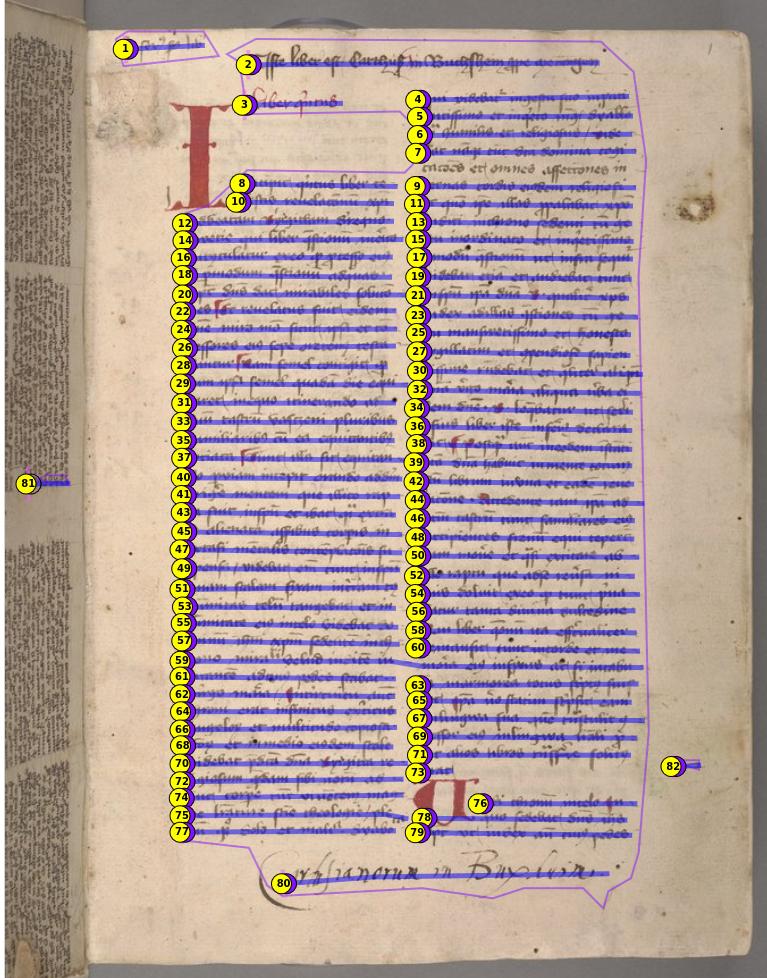

Now, let us turn to our explorations with Transkribus. As in eScriptorium, the HTR workflow in Transkribus involves two main steps: detecting text regions and lines, followed by transcription. Segmentation can be carried out as a separate step or combined with transcription in a single process. By default, Transkribus uses a pre-trained segmentation model, though users can also train custom models tailored to their specific material. The recommended dataset size for training a new model is approximately 50 pages.

We tested the default segmentation mode in Transkribus and encountered segmentation challenges similar to those observed in eScriptorium. In particular, the default segmentation model performs best on single-column layouts. In the example shown below (see Figure 11), it incorrectly interpreted both columns of a page as a single region. As a result, the reading order became distorted: instead of reading the columns top-to-bottom, the engine processed the text line-by-line across the full page width from left to right. This produces transcriptions that are jumbled and difficult to interpret.

However, unlike the segmentation model in eScriptorium, the Transkribus model appears to handle two-column layouts more effectively - provided no additional text elements, such as titles, are present.

Transkribus also allows users to adjust parameters for layout analysis. Despite experimenting with these settings, we were unable to achieve the correct number of segments on a manuscript page that included a title. This suggests that more robust performance on complex layouts is likely only achievable by training a custom model tailored to the specific data. In our tests, we chose to force the model to detect “multiple” segments - see Figure 15 for the results.

Now let us turn to our experiments with the transcription models in Transkribus. As in our tests with eScriptorium, we evaluated several HTR models to assess how well they perform on Latin manuscripts. One of the best-performing models was TrHtr Titan I bis, released in April. This was trained on a large, balanced dataset that includes both printed and handwritten documents, covering historical as well as modern sources. The platform classifies it as a “super model,” meaning that access requires a subscription.

To explore a free alternative, we also tested a pyLaia-based model available in Transkribus: Medieval_Scripts_M2.4. Trained on 24,764 pages, this model was developed as a general-purpose HTR solution for medieval Latin scripts.

In terms of interface, Transkribus offers functionalities similar to those of eScriptorium, but it lacks some useful features. For instance, it does not currently support the direct comparison of more than two transcriptions, nor does it highlight the differences between them. Another helpful feature present in eScriptorium but missing in Transkribus is the close view option; in Transkribus, the only way to inspect individual lines is to manually zoom in on the highlighted text.

Turning to the transcriptions themselves, we observed that the Titan I bis model handles abbreviation expansion inconsistently - likely reflecting the diversity of its training data. In one example (see Figure 17), the model successfully expands common abbreviations such as et and us, demonstrating its capacity to interpret these forms correctly. However, in another case (see Figure 18), the same abbreviation signs - such as ꝰ (us) and ꝭ (-us) - are left unexpanded, along with several others. This inconsistency suggests that the model does not apply a uniform rule for abbreviation expansion across different documents or contexts, which may require additional manual correction during post-processing.

Another notable feature of the Titan I bis model is its attempt to transcribe paragraph signs (¶) to reflect the original structure of the text. However, the model is not always consistent: it occasionally inserts the sign correctly, but at other times omits it or places it incorrectly.

This tendency can also result in transcriptions that include unexpected characters, such as < or |, which are not present in the original manuscript.

Like the Titan I bis model, M4.2 also shows inconsistency in handling abbreviations. For example, the abbreviation ꝰ (used for us) is expanded in the word revelatus, but left unchanged in auitꝰ, despite being the same abbreviation.

In other cases, the model fails to expand the abbreviation entirely and sometimes omits diacritics as well (see Figure 24). These inconsistencies can make it difficult to produce clean, uniform transcriptions - particularly when working with larger datasets or aiming to support full-text search across the material.

The challenges we encountered highlight how off-the-shelf models often fall short when applied to specialised manuscript collections with complex layouts and distinctive scribal practices. These limitations underscore the value of developing tailored models to improve transcription quality.

Testing TrOCR

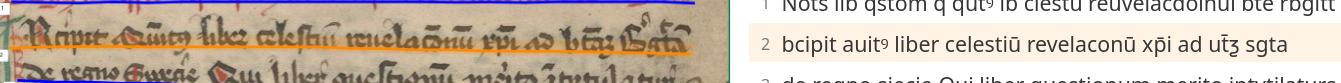

We also explored a third approach using transformer-based models outside the two major platforms. The TRIDIS model is available in a version built with Microsoft’s TrOCR framework, a transformer-based OCR system. This alternative, trained on the same dataset as the Kraken version, combines a Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder with a decoder based on a medieval Latin RoBERTa language model. According to reported evaluations, the TrOCR-based model is expected to slightly outperform its Kraken-based counterpart.

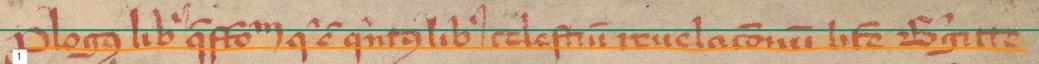

To use the TRIDIS TrOCR model for transcription, we first segmented the manuscript pages using the BigLAM YOLO model. Trained on the CATMuS Medieval Segmentation dataset, this model can distinguish between 18 different layout elements - such as heading lines, standard text lines, marginalia and numerical annotations.

At present, there is no graphical interface that fully integrates YOLO-based segmentation with TrOCR-based transcription. However, for those interested in exploring how the BigLAM model performs, a demo is available on Hugging Face.

Like the other segmentation methods we tested, YOLO produces outputs consisting of regions and the elements contained within them. Unlike the models in eScriptorium and Transkribus - which recognize regions and text lines - YOLO also provides element-level classification, identifying components such as lines, marginalia or initials. In Transkribus, achieving this level of detail requires training a separate “Field” model. Understanding the structural layout of a document is crucial, as it allows the detected lines to be organized into coherent text before the HTR step.

As noted, there is currently no interface that directly integrates TrOCR and YOLO models. As a result, users must programmatically extract lines from the manuscript pages, determine the correct reading order, and then run recognition on the extracted line images.

In our tests, we performed only steps 1 and 3 - line detection and text recognition - without automatically correcting the reading order. However, YOLO’s ability to label different parts of a page offers a valuable foundation for automating the reading order in future workflows.

The HTR model we tested is available on Hugging Face under the name: magistermilitum/tridis_v2_HTR_historical_manuscript. Compared to the Kraken model trained on the same dataset, the TrOCR version successfully corrected many transcription errors that Kraken failed to resolve. For example:

| Example | Source | Transcription |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manual | -cionem peccatorum de medio ignis zeli dei |

| Kraken | cionem pecctorum de Medioignis zeli Dei |

|

| TrOCR | cionem peccatorum de medioignis zeli dei |

|

| 2 | Manual | Liber quintus |

| Kraken | Liber quantus |

|

| TrOCR | liber quintus |

|

| 3 | Manual | de regno Swecie Qui liber questionum merito intulatur |

| Kraken | de regno Girecie Rui liber questionim meito intytulatur |

|

| TrOCR | de regno Swecie Qui liber questionum merito intulatur |

|

| 4 | Manual | Liber quintus |

| Kraken | Riber qntus |

|

| TrOCR | Liber qſtionu |

|

| 5 | Manual | Liber quintus |

| Kraken | Riber qntus |

|

| TrOCR | Liber qſtionu |

In some instances, TrOCR improved the transcription but did not fully correct the text:

| Source | Text |

|---|---|

| Manual | -bantur Nam semel contigit quod |

| Kraken | bautur Fulam semel contigit quom |

| TrOCR | vantur suam semel contigit quod |

In a few cases, TrOCR introduced completely incorrect words. For example, it transcribed “videlicet” instead of “sed”, which Kraken had correctly recognized:

| Source | Text |

|---|---|

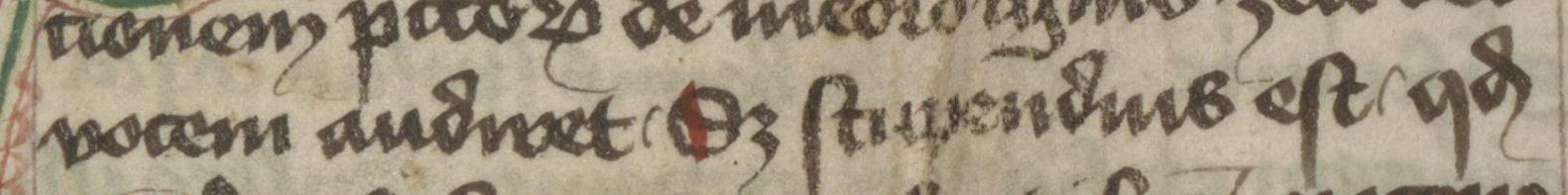

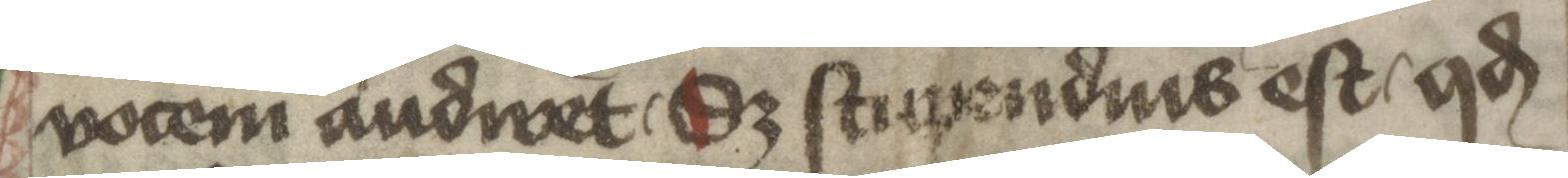

| Manual | vocem audiret Sed stupendius est quod |

| Kraken | votem audiret / sed scupendius est quod |

| TrOCR | vocem audiret / videlicet stipendius est / quod |

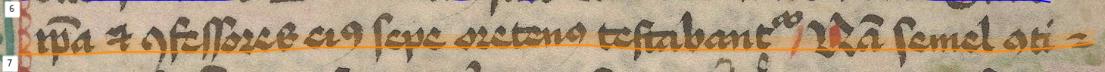

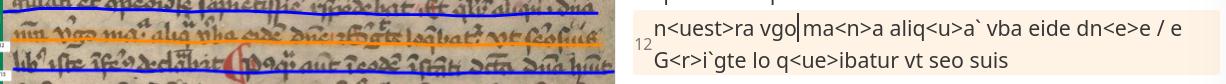

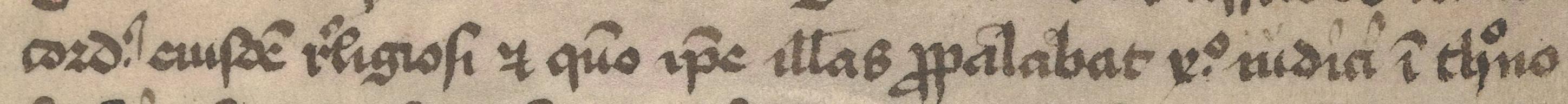

As with other frameworks, the quality of segmentation has a major impact on HTR performance. When the manuscript text is relatively straight, YOLO’s output for a line typically includes only that line, with minimal noise (see Figure 26). In skewed documents, however, the detected line may accidentally include fragments from the lines above or below, as illustrated in Figure 27.

To reduce the impact of this added noise, an additional preprocessing step can be introduced before text recognition. For testing purposes, we used a model available on Hugging Face: Riksarkivet/yolov9-lines-within-regions-1. (Note: this model was trained on a different dataset and is included here solely for experimental purposes.)

Figure 27 shows the “DefaultLine” region recognized by the medieval-manuscript-yolov11 model, while Figure 28 presents the same image cropped to remove surrounding noise. Although the model was not specifically trained on this type of manuscript, it performed adequately for testing purposes.

Comparison after masking:

- Before (TrOCR): vocem audiret / videlicet stipendius est / quod

- After (cleaned TrOCR): yocem audiret / sed stipendius est quod

- Gold: vocem audiret Sed stupendius est quod

Masking redundant text helped clean up the transcription and corrected the previously mistranscribed word “videlicet” to the correct “sed.” However, it also introduced a new error in the first word, which had previously been transcribed correctly. This highlights the importance of experimenting with different cropping and masking techniques, as well as the critical role of image preparation in the HTR pipeline.

A valuable tool for managing this HTR pipeline is the HTRFlow Python package, developed by our colleagues at the National Archives of Sweden’s AI lab. HTRFlow simplifies the customization and management of HTR workflows by using a configuration file in which each step - such as segmentation or recognition - is defined as a modular component. This design allows users to flexibly adapt and experiment with different models or processing steps, without needing to rewrite code for every adjustment.

Comparing outputs: Kraken, pyLaia or TrOCR?

The performance of the HTR models we tested reflects the differences in their training data, transcription conventions and underlying architectures:

TRIDIS TrOCR consistently delivered the most complete and accurate transcriptions. It handled abbreviations - such as “xp̄i” - by expanding them correctly to “Christi,” and even resolved more complex abbreviations into their full forms with remarkable consistency.

Kraken-based TRIDIS produced results similar to the TrOCR version but was more prone to occasional character-level errors, such as misrecognizing single letters or ligatures.

Kraken CATMuS faithfully preserved original abbreviations and special characters, making it suitable for researchers interested in palaeographic detail and scribal practices. However, its literal output may require additional editorial interpretation for those less familiar with medieval Latin conventions.

Transkribus Titan I bis generally yielded readable, standardized text and attempted to encode layout features (e.g., paragraph marks or vertical bars). Although its transcriptions were often clear, the model sometimes introduced incorrect expansions or misreadings, and its layout markers were not always reliable.

Medieval_Scripts_M2.4 (pyLaia) was the least reliable of the tested models, particularly in segmentation. It struggled with accurate line breaks and produced more errors compared to the other tools.

All models exhibited occasional spelling inaccuracies, spacing errors, misreadings and inconsistent abbreviation expansions. Overall, the TrOCR version of TRIDIS offered the best balance between accuracy and normalization - simplifying complex elements without introducing excessive distortions - which makes it a strong candidate for further fine-tuning in the future. The Kraken CATMuS model provides a closer visual match to the original manuscript, preserving intricate glyphs and diacritics, which may be especially valuable for manuscript-focused research. The Transkribus models tended to simplify special characters more aggressively, which improved readability but sometimes flattened palaeographic nuance and distorted visual elements.

In the appendix below you can observe exemplary outputs from the four models alongside the manually curated “gold standard” transcription for direct comparison.

Next steps and future work

Our experiments yield promising results, particularly with models like TRIDIS TrOCR, which strike a good balance between legibility and historical accuracy. However, variability in script styles, layouts and editorial conventions remains a significant challenge.

Moving forward, we plan to explore the following options:

Fine-tune models on representative samples from KB’s collections.

Develop annotated datasets featuring both diplomatic and semi-diplomatic transcriptions.

Investigate hybrid workflows that combine HTR with expert human validation.

Explore user-friendly tools for viewing, comparing and correcting transcriptions.

By continuing this work - and sharing both our successes and setbacks - we hope to contribute meaningfully to digital manuscript studies and improve access to KB’s medieval heritage collections. We welcome feedback from other researchers and institutions working with medieval Latin manuscripts and HTR. If you’re interested in collaboration, don’t hesitate to get in touch at kblabb@kb.se.

Appendix: HTR Model Results with Manual Benchmark

| Tridis_v2 | tridis_v2_tr_ocr | Catmus-medival-1.6.0 | Titan I bis | m4.2 | Manual (Gold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| liber primus | liber primus | Liber primus | Liberprimus | Liber primus | Liber primus |

| tupor et muralia judita sunct in tram | Stupor et miralia vidita sunt in terra | tupor et miralia uidita st̾ ĩ tra | tu por et miralia iudita sunt in tra | Stupor et miraliauidita ſti tra | Stupor et mirabilia audita sunt in terra |

| nostra mirabile si quidem erat quod ze | nostra mirabile siquidem erat quod ze | nr̃a Mirabile si quid̃ erat ꝙ ze | nostra mirabile si quidem erat quod ze | nostra mirabile siquidem erat quod ze | nostra mirabile siquidem erat quod ze- |

| lator legis morses igneam in vl | lator legis morses ignea in vl | lator legis moyses igneã in ul | lator legis moyſes igneā in vl | Dlator legis moyses ignea in vl | lator legis moyses igneam in vl- |

| cionem pecctorum de Medioignis zeli Dei | cionem peccatorum de medioignis zeli dei | tiõnem pcc̃oꝵ de medro ignis zeli dei | tionem pctoro de mediovinis zeli dei | cionem patorum de medioigus zeli dei | cionem peccatorum de medio ignis zeli dei |

| votem audiret / sed scupendius est quod | vocem audiret / videlicet stipendius est / quod | uocem audiret. S scupendiis est qd | || vocem audiret | Dz §tuyenerins eſt | quod | vocem audiret Eʒ ſtuprudius eſt quod | vocem audiret Sed stupendius est quod |

| huiles hodie et mansueti spiritu vocem | humles hodie et mansueti spiritu vocem | hiunles hodie et mansueti spũ uocem | huiusles hodie et mansueti spiritum vocem | hunles hodie et mansueti spum vocem | humiles hodie et mansueti spiritu vocem |

| ibu Christi Dei et homum aveuit ut olim | Jhesu Christi dei et hominum audint ut olim | ihũ xp̃i dei et homu audĩt ut olim | Si hū xpi dei et homi auduit ut olim | hu xxi dei et homi auduit ut olim | iesu christi dei et hominis audiunt vt olim |

| Tridis_v2 | tridis_v2_tr_ocr | Catmus-medival-1.6.0 | Titan I bis | m4.2 | Manual (Gold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iste liber est Carthuser in Buchshein prope Meningen | Iste liber est Carthuses in Bouchshem prope Meningen | Iste liber est Carthus in Buchshem ꝓpe memugen | Iſte liber eſt Carthuͤß in Buchſheim ſpe wenigen | Iste liber est Carthusz in Buchshein prpe Meningen | Iste liber est Carthusiensis in Buchshem prope memingen |

| liber quantus | liber quintus | Riber qntus | Tiberg’ntus | Riber qntus | Liber quintus |

| ncipit quantus liber te | Incipit quintus liber te | ncipit qntus liber ce | incipit (qͥntus liber te | ncipit quntus liber te | Incipit quintus liber ce- |

| lestis revelacionum Christi | Lestis revelacionum Christi | lestis reuelacõnũ xpi | ¶ leſtis reuelatōnum xp̅i | Clestis revelacionum xxi | lestis reuelacionum christi |

| adbeatam Byigictam drequo | ad beatam Bycam dregno. | adbeatam Bycgittam dregno. | abbeatam bydgickam d̾ regno | adbeatam Byigittam dregno | ad beatam Byrgittam de regno |

| siretie qui liber questionum meico | sroetie qui liber questionum merito | siretie qui liber q̃stionũ melco | ſwetie qui ſiber q̄ſtionu meito | swetie am liber qſtionu meico | swecie qui liber questionum merito |

| intyntulatur exeo quam processo eius | intyculatur ex eo quod processo ejus | intyculatur exeo ꝙ ꝓcessꝰ eiꝰ | intyculatur exeo quod processo eius | intyculatur exeo quod processo eius | intytulatur ex eo quod processus eius |

| et prmodum questianum adquas | est postmodum questionum adquas | ẽ ꝓmodum q̃stianũ adquas | est primodum quaestionum adquas | permodum questionum ut infra sequi | est per modum questionum ad quas |

| xhrist dominus dac nirabiles soluto | sept dominus dati mirabiles soluto | xp̃t dñs dac mirabiles solutõ | Xpt dominus dach mirabiles ſoluto | xpc dominus dac mirabiles soluto | christus dominus dat mirabiles solucio- |

| nes et revelatus fuit eidem | nes et revelatus fuit eidem | nes ¶Et reuelatus fuit eidem | nes ¶ Et reuelatus fuit eidem | nes set revelatus fuit eidem | nes Et reuelatus fuit eidem |

| domine miro oson sicut ipsa et con | domine miro nostro sicut ipsa et con | dñe miro mõ situt ipsa et cõ | dn̄e miro mō ſitur ip̄a et to | dne miro mo situc ipsa et co- | domine miro modo sicut ipsa et con- |

| fessores ejus sepe oretenu resta | fessores ejus sepe oretenus resta | fessores eiꝰ sepe aretonꝰ resta | feſſores eius ſepe oretem teſta | feſſores ei ſepe cretens reſta | fessores eius sepe oretenus testa- |

| bautur Fulam semel contigit quom | vantur suam semel contigit quod | bantur Iam semel contigit ꝙ | bantur Nam semel contigit ꝙ | vantur Nam ſemel contigit q | -bantur Nam semel contigit quod |

| Tridis_v2 | tridis_v2_tr_ocr | Catmus-medival-1.6.0 | Titan I bis | m4.2 | Manual (Gold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eloga libero quesato que e quenta libe celestin reuela conun bete vegit | Ploga libras questionem, qui cum quintalibus celestium revelacionum beate Berengitte | plogꝰ lib̾ q̃sto ͫͫ q ẽ qntꝰlib celestiũ reuelacõnũ bte Bgitte | plogꝰ lib q̄stōm qͣ ē qᶦntꝭ lib* celestium reuelacionum btē Bˀgitte | Nots lib qstom q qutꝰ ib clestū reuvelacdoinui bte rbgitt | prologus libri questionum qui est quintus liber celestium revelacionum beate Birgitte |

| cipit vitus liber celestium revelacionum Christi ad batam Botam | Precipit adecuitus liber celestivi revelacionum Christi ad vestram bergertum | Acipit adũitꝰ liber celestiũ reuelacõnũ xp̃i ad bt̃a Egtã | Mcipit a Quĩtꝰ liber celeſtuĩ reue la cõnũ xp̄i ad bt̄az Sgͣtā | bcipit auitꝰ liber celestiū revelaconū xp̄i ad ut̄ƺ sgta | INcipit Quintus liber celestium reuelacionum christi ad beatam Birgittam |

| de regno Girecie Rui liber questionim meito intytulatur | de regno Swecie Qui liber questionum merito intulatur | de regno Groecie Qui liber questionũ meito ĩtytulatur | de regno swecie Qui liber questionū meito ītytula tur | de regno siecie Qui liber questionum merito intytilaturs. | de regno Swecie Qui liber questionum merito intytulatur |

| exra eo quod processus eius est per modum questionum ad quas x dominus dat nostri et | ex eo quod processus eius est per modum questionum ad quas xl. dominus dat iii et | ex eo ꝙ ꝓcessꝰ eiꝰ ẽ ꝑ modũ q̃stionũ ad qͣs x dñs dat mĩr | ex eo quod processus eius est per modum questionum ad quas Cristus dominus datum im | ex eo quo processus eius en per modum questionum ad quas e domins dat mi | ex eo quod processus eius est per modum questionum ad quas christus dominus dat mira- |

| biles soluciones . Et revelatus fuit eidem domine miro modo sicud | viles soluciones / Et revelatus fuit eidem domine miro modo situd | biles solucões. Et reuelatꝰ fuit eidẽ dñe miro modo Sicud | biles solucciones Et reuelatus fuit eidem domine miro modo Sicud | biles soluciones Et revelatus fuit eidem domine miro modo Sicud | -biles soluciones Et reuelatus fuit eidem domine miro modo Sicud |

| ipsa et confessores eius sepe oretenus testabantur Ma semel conti | ipsa et confessores eius sepe oretenus testabantur / Wansemel | ip̃a ⁊ ꝯfessores eiꝰ sepe oretenꝰ testabant Nã semel ꝯti ⁊ | ipsa et confessores eius sepe oretenus testabantur. Nam semel conti | ipsia et confessores eius sepe oretenus testabantur Nam semel conti e | ipsa et confessores eius sepe oretenus testabantur Nam semel conti- |

| git quod cum ipsa quadam die equataret in equo itermerando ad suum | sit quod cum ipsa quadam die equitaret in equo Itermerando ad suum | git ꝙ cũ ip̃a quada die cqͥtaret ĩ equo itmerando ad suũ | Egit quod cum ipsa quadam die equitaret in equo itinerando ad suum | git quo cu ipsa quadea die equataret in equo itmerando ad suum | -git quod cum ipsa quadam die equitaret in equo itinerando ad suum |

| castrum wadzsta plribus fralidibus cum ea equitantibus sociata tunc illa | castrum Wadzsten pluribus frantibus cum ea equitantibus sociata, tunc illa | castrũ wadste płibꝰ frãliai̾bꝰ cũ ea eq̾tãtibꝯ soci̾ata. tũc illa | caſtiū wadꝫ stꝭ pl̄ibro fālicaibꝰ cū ea eꝗtcīti bo ſociata. tūc illa | castum wadstuis plibs frailiaribus cum ea cstanti bius socirata. tumc illa | castrum wadzsteni pluribus familiaribus cum ea equitantibus sociata tunc illa |

| sic eutando per viam Incep orando ad Deum erige mentem suam | sic equitando per viam. Incept orando ad Deum erigeretur mentem suam. | sic eq̾tando ꝑ uiã. Incepͭ orando ad deũ crige ͨ mentẽ suam. | sic equitando per viciis incepto orando ad deum eriget mentem suam | sic eostando pruia. inceps orando ad deum erigeus mentem suam | sic equitando per viam Incepit orando ad deum erigere mentem suam |

| que illico rapta fuit in spiritu etibat quai extra se alienata a | que illico rapta fuit in spiritu et ibat quam extra extit se alienata a | que illico rapta fuit ĩ spũ. ⁊ ibat qͣi ext̾ se alienata a | que illico rapta fuit ĩ spiritū. ⁊ ibat qͣi ext se alienata a | que illico rapta fuit in sptiu. Rwat quam exter se alienata a | que illico rapta fuit in spiritu et ibat quasi extra se alienata a |

References

Acknowledgments

Part of this development work was carried out within the HUMINFRA infrastructure project.

Citation

@online{sikora2025,

author = {Sikora, Justyna and Haffenden, Chris and Böckerman, Robin},

title = {From {Parchment} to {Pixels:} {Testing} {HTR} for {Medieval}

{Latin} {Manuscripts} at {KBLab}},

date = {2025-06-11},

url = {https://kb-labb.github.io/posts/2025-06-11-from-parchment-to-pixel/},

langid = {en}

}